Preservation – but at what cost?

Preservation - but at what cost?

by Emily Koh

Reinvention is taking place at the Keong Saik Bakery. There is a convergence of two identities, the old and the new, and both are changing, themselves and each other. There is a kind of charm that wafts through the bakery when you step inside, tender tendrils unfurling and curling their way around the edges of memory, of nostalgia—familiarity (words like ‘attap chee’, ‘kueh salat’, ‘chendol’, ‘kopi-o’) but also an unsettling strangeness (“we use beans roasted the local way in the coffeeshops, but we brew them using an Italian espresso machine”). I don’t really know what to expect, and as I look over the delicious pastries behind the glass casing, I realise that I cannot quite put my finger on what I am smelling; I think it smells something like excitement.

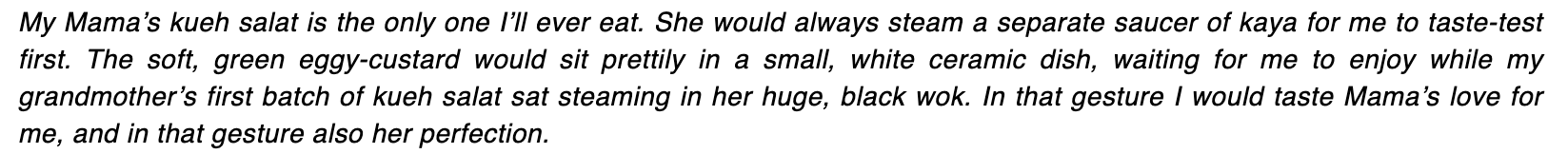

The novelty steadily dissipates, however, when the time comes to actually choose. I look hard at what is on display (I scrutinise); I have to order (and soon!) before the queue behind me gets any longer. The pleasant stimulation brought about by innovation, of creativity, to bring together a mixing of the old and the new has given way to a kind of sober clarity. I ask myself honestly: do I really want to eat an Attap Chee Rose Cheesecake or a Mama’s Kueh Salat? (Attap chee, bandung and cheese, quirky combination or fatal? And is Mama’s Kueh Salat kueh salat at all? And who is Mama? Whose Mama is it?) Or do I really want to eat a Chendol Delight? (What on earth is a Chendol Delight? Chendol is delightful enough as it is; is Chendol Delight going to turn out horribly wrong like Tuna Surprise? I shudder at the thought.) The final question that nags at me is: Why do all of these fusion cakes have genoise in them? I end up ordering a teh o ice limau, for the reinvented price of $2.50.

I am sitting opposite Kervin right now, the Purist, period, and not just the Laksa Purist. Just earlier, I was telling him about Cookie Museum’s “amazing nasi lemak cookies!” where in one bite you can actually taste separate different ingredients, to which he exclaimed indignantly, “If you want to eat nasi lemak, why don’t you just eat nasi lemak?!” Which is why I wonder: why reinvent? Why do people engage in reinvention? What is wrong with the real thing, with the original? Because if there is nothing wrong with it, then why reinvent it? And if there is something wrong with it, why not just let it die out?

Is reinvention to shock and to surprise? Or is it for survival? Is the old fighting to stay relevant? Or is the new trying to discover itself? The interesting thing is that reinvention can take place both ways: the old reinventing itself by the new, and the new by the old.

Before we leave, Keong Saik Bakery offers us a teasing taster’s portion of two new cakes that they are trying to roll out: Gula Jawa Sticky Rice cake and a Mango Mousse Star Anise-something-whatever. We each choose our poison and the experience is… underwhelming. I cannot get drunk on the thick, syrupy richness of gula melaka this way—in a block form like this there is no liquid intoxication. And the fresh, honeyed sweetness of mango fights for attention with the subtle headiness of star anise—which gets drowned out and goes under.

I leave the bakery with more wondering: with each round of reinvention, are we moving further away from the original? As we try to preserve—something, anything—through our reinventing, what have we also lost? Is compromise and dilution the only way we can keep what some of us think is of value? Why does classic not have currency in the minds of the young?

I wander along the row of shophouses that line Keong Saik Road, walking on ceramic tile that ghosts have dusted over with their breaths and their footprints, and I wish for a kind of recklessness to return. Just as the young seem to innovate based on impulse and energy, why don’t the old fight with the kind of desperate recklessness that can come only with age and with loss?